In the spirit of keeping this an open dialogue, commenting is enabled at the bottom of this post so that readers can contribute their thoughts & questions for our Student Scholar Fellow.

Merlin Student Scholar Fellow: Research & Writing

“If Socrates Were a Psychiatrist…”

Inspired by her interest in philosophy & psychiatry, Merlin Student Scholar Fellow Julianna Breit explores some of their similarities & differences and how practitioners in both are obsessed with “The Good Life.”

When I first started philosophy, I thought of philosophers as psychiatrists. Both encourage the development of self-knowledge. Socrates encouraged Euthyphro to consider what piety meant to him during the personal crisis of his father’s trial, and sitcom therapists often challenge characters to reconsider their actions and values with respect to a personal crisis and its consequences. Definitionally, as “lovers of wisdom,” philosophers delve deeply into what comprises human virtue, intelligence, and ultimately, practice. Psychiatrists, as “caretakers of the soul,” direct patients towards actions that are motivating, reflective, and fulfilling.

Frankly, both are obsessed with “The Good Life,” even if it is not called such clinically.

Philosophy & Psychiatry

Similarities

Whether enclosed behind the prestigious bricks of universities or comforted on the elegant couches of psychiatric offices, humans reflect on their own experiences and analyze them in the context of the world to find patterns. Both philosophy and psychiatry require an intimate self-knowledge, more rigorous and conscientious than mere facts about favorite colors and birthdays.

“Know thyself, but not via flash cards,” both philosophers and psychiatrists proclaim while you do the deep, dark, and difficult work of self-analysis.

Assuredly, there is a lot to think about when reflecting on philosophical truths or therapy homework.

Before people can understand others’ irritating behaviors or even question their own mental awareness, they position other people in the context of their own lives. By establishing others’ relationships to us, we can analyze them as participants in each of our lives, and understanding our own lives is more accessible than trying to understand others’. We have most control over our own actions. Oftentimes, changing our actions towards others reveals not only something about ourselves, but also something about our environment and the people in it. Consequently, both philosophers and psychiatrists promote self-analyzing first because it’s the lived experience you know and study best. It’s the one you can pull the most detail, perspective, and consequence from, making it an ideal starting point for analyzing the rest of the world. This level of truth-seeking requires relentless inquisitiveness, detailed observation, and critical analysis – the marks of a successful philosopher and an accomplished psychiatrist.

Moreover, philosophers and psychiatrists, seemingly, practice similar diagnostic processes. They both utilize professional schools of thought to identify and approach issues. They both extensively question to further understand. Sometimes, not all questions are answered, but the act of questioning initiates a continual process of understanding.

In principle, thought experiments in philosophy are like therapy. Thought experiments present a theoretical idea to further understand an issue by isolating a problem, and therapy encourages the isolation of a particular action in attempt to reorient behavior.

Both psychiatry and philosophy emphasize a healthy amount of doubt so that the intellectual process of self-discovery may continue, free of assumptions which may inhibit the learning process.

So, the critical question becomes, “How are philosophers different from psychiatrists or other clinicians?” Does philosophy have something unique to present, distinct from the social functionality of modern scientific practice?

Philosophy & Psychiatry

Differences

Despite the shared aim on “The Good Life,” philosophers have more freedom to explore lofty ideas than psychiatrists do.

Consider writing styles. Philosophical writing utilizes logically developed, analytical arguments which can lead to broad, open-ended questions; whereas, clinical notes and lab reports begin with a broad topic, summarize obtained results, and directly report the statistical significance of the original hypothesis. While conclusions in philosophical papers can in some ways be speculative, theoretical, and broad, lab reports are very conservative, concrete, and narrow. They answer a yes-or-no question instead of contributing to an open-ended one.

Even though philosophers may continue to explore a philosophical question for decades and even centuries, psychiatrists operate within the timeline of a human life.

In the case of mental health crises, psychiatrists do not have decades to determine the inhibition of the patient’s “Good Life.” They must propose a diagnosis and proceed as if it were the correct answer to their clinical question. While questions are the measure of the thinker, results are the measure of the doctor. Sometimes to achieve results, psychiatrists must entertain the answer more than the question – the diagnoses that will be the most effective instead of the detailed questions behind the patients’ motivation and value systems.

Some practices of philosophers and psychiatrists clash despite the similarity in questioning and self-analysis. Philosophers can embrace the many years and continual questions because the process of questioning is inherently valuable. This process incorporates critical thinking, thorough analysis, and continual reconsideration – all qualities of philosophical reasoning. Psychiatrists, however, question to achieve conclusive results.

Distinct from answering questions, doctors need quickly identifiable consequences to their philosophical inquiries. There would be no psychiatric practice for those who bill by the eons instead of the hour. Conclusive results are quantifiable, assessable, judgeable, and frankly, the modern way of measuring “The Good Life” physically.

We take time to understand ourselves as functioning humans, but only a reasonable amount of time for a life on a stopwatch where other physical needs, such as food, exercise, and education fight for precedence.

Despite the deeply psychic element, psychiatrists tend to humans as tangible beings – as observable, social, interactable beings in a constructed society. Human sociability is observed in a physical body, in a physical world. When this type of “Good life” is malfunctioning, it is evident in a physical environment where one person’s actions empirically affect others. Even though philosophical thought contributes to more well-rounded, functioning thinkers who strive to live better lives, their questions also result in something very ethereal – a “Good Life” independent of a world where anyone else lives.

Regardless of whether the world is physical or people are social, a philosopher would philosophize with no one else in existence.

Descartes continued to think despite and, in some ways, because of his doubt of others’ physical presence. I am not equally convinced that people would go to therapy if their actions did not impact their physical and social well-being.

With respect to the different requirements of philosophical ideas versus therapeutic needs, philosophers and psychiatrists demand different relationships with the people they assist. In many ways, philosophy assumes the capacity to converse. In his dialogues, Socrates assumes that his audience has the capacity to understand complex distinctions in ideas. While questioning their virtue and critical thinking, he evaluates their intellectual acuity rather than their physical (including social and emotional) wellness. In philosophical practice, there are assumptions about the basic understanding of human experience as well as the ability to analyze it intellectually and critically. Psychiatrists do not have the same assumptions. Instead, they need to assess the patient’s capacity to distinguish and dialogue before any self-analysis may begin. The psychiatrist must assess the patient’s boundaries for sharing and understanding before they can assess the patient mentally, emotionally, and rationally.

While the psychiatrist’s care for the patient’s welfare mirrors Socrates’ academic mentorship for achieving thorough self-examination, the psychiatrist does not have the same ability to converse freely because they cannot as strongly enforce expectations for interpersonal behavior that permit candid feedback.

After all, a professor in office hours interacts with a student more bluntly compared to a psychiatrist with a patient in therapy because university life implies certain performance expectations of students; at the initial interview, psychiatrists cannot as strongly expect professional or intellectual behavior from their patients because they are still unaware of the patient’s emotional sensitivities and rational capacities. Only after they assess and reassess the patient’s boundaries can the psychiatrist freely advise about living a healthier life.

Ultimately, psychiatrists and philosophers operate within different loci of control.

Frankly (and probably not surprisingly), therapy is a personal endeavor, and its customized treatment works for you and only you. By the end of a series of clinical sessions, the goal of therapy is to achieve, “Your Good Life.” As much as I dislike the simplistic social solution — “Worry about yourself and no one else,” that’s the domain psychiatrists can operate within because they are responsible for directing your actions; they are treating you – no one else. Philosophy, however, aims towards “The Good Life” – recording principles for everyone, no matter the circumstance. While utilizing the personal experiences as a launching pad, philosophy strives to generalize universal directions as well as providing personal standards.

The Good Life v. My Good Life

Concluding Thoughts

It’s not philosophy’s job to rest content with only the personal; it’s also philosophy’s job to inform generations of deliberate thought. As adeptly and pungently stated at a recent Think-And-Drink, “Who cares about tomorrow? This is about philosophy!” Sometimes, the diagnostic eye of the psychiatrist is needed in place of the universalizing arms of the philosopher. We’re not always going to get an answer to our life problems from those who think for eons about the implications of an action. Consequently, it’s not always the philosopher’s job to give us an answer. It’s the job of the philosopher to integrate personal experiences in a way that relates its consistencies to others and constantly reassesses the definition of “The Good Life” in a world that’s personal, messy, and particular.

Personal experience is the test of good philosophy. For all its universalized goodness and lofty ideals, philosophy does not mean much if it cannot be applied to personal life. If the model of “The Good Life,” cannot not help us achieve, “My Good Life,” then it needs to be reassessed. Philosophy can take eons because it needs to account for the circumstances of the lives it fails. If everyone is supposed to achieve “The Good Life,” then it needs to have goals that are potentially achievable for those in all circumstances – everywhere, any time. Because psychiatry is concerned with “My Good Life” from the beginning of its questioning, there is not the same fear that it will not account for my individual needs and desires.

Nonetheless, philosophy works as a universal system because there are universal experiences among individual human lives. For a start, everyone is born, and everyone dies. And, at some point, we all must deal with grief – even if we deny it until we are depressed, repressed, or confused.

Grief exemplifies a common issue philosophers and psychiatrists must address because it is a universal experience that deeply affects individual lives.

Before psychiatrists can understand the effects of grief on an individual, they need to understand the general impacts of grief. They need to understand the experiences grief undermines and the values underlying its experience. Regardless of whether they consciously recognize it, psychiatrists consider the philosophical implications of an emotion or trauma every time they treat a patient; then, they reassess the general experience in line with the particular patient scenario. After assessing the patient’s emotional capacity, psychiatrists dialogue with them about advantageous actions for achieving the “The Good Life,” in context to “Your Good Life.”

As “caretakers of the soul,” psychiatrists encounter the “love of wisdom” or philosophy, in a way that’s beautifully personal. There are universal aspects of human condition that can only be experienced personally, such as grief. As soon as we try to separate emotions from human condition, they lose some of their impact and relatability. Grief experienced is more pungent than grief written, and grief written is effectual because grief can be experienced. Psychiatry without the practice of philosophy would be ungrounded in a human experience with no universalized understanding, and philosophy without psychiatry might not touch as many aching people. They both contribute something critically beautiful to the world. Philosophy informs universal practice, and psychiatry implements philosophical practice in personal lives. The wisdom of philosophy is enshrined in the souls of people that bear lived experience, personal awareness, and world perspective.

Perhaps, the relationship between philosophers and psychiatrists is that psychiatrists act as philosophers sometimes.

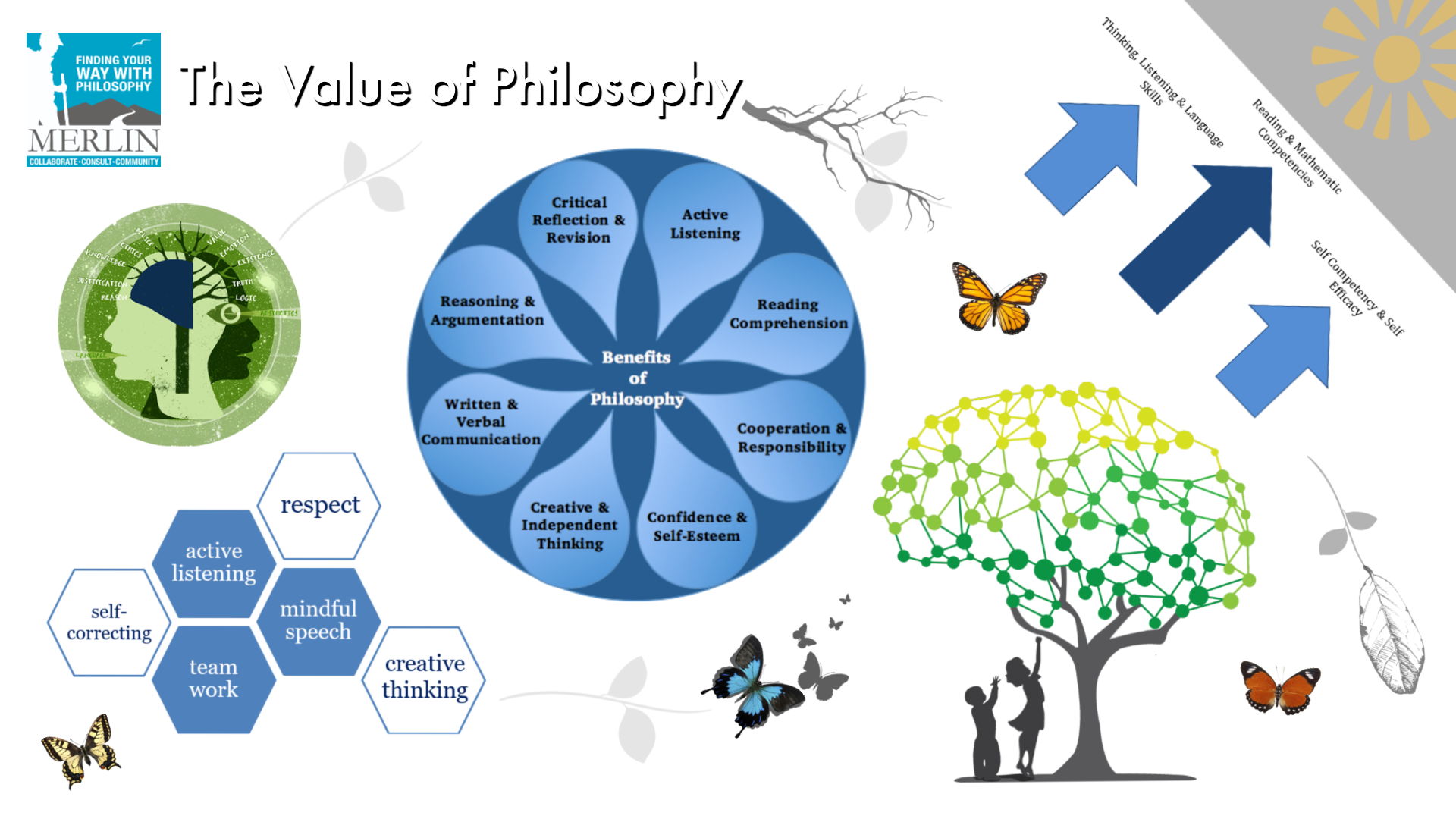

Philosophy necessarily contributes to better thinkers and more self-aware citizens. Without philosophers, we might not have effective psychiatrists. The detailed questioning, critical analysis, and universalizing experiences of philosophy provide a foundational practice for all professions which seek to interact, teach, or expand on lived human experience. After all, there cannot be a PhD in any study without the Ph!

Ultimately, philosophy informs our lives and professions more than we think. Perhaps, with more consideration, we can each discover the special relationship philosophy has to our own professions and better understand the accountability philosophy instills in our own lives!

Special thanks to all the members of the Merlin community who attend the Think & Drinks and continue to inspire my philosophical curiosity! This blog is a product and expansion of some of our on-going conversations so that we can achieve some sort of satisfactory conclusion before this eon is over! Thank you to David Nowakowski, who mentored my philosophical reasoning throughout this project and provided essential feedback toward this shared product! Thank you to Marisa Diaz-Waian, who fosters the development of “The Good Life” for all of us in the Helena community and beyond! Thank you to Barry Ferst, who playfully inspired this blog’s title! Finally, thank you to my beloved philosophy friends (Claire, Greyson, and Jake) as well as my dedicated mother, who for the love of all things philosophical, took the time to edit this writing during their holiday from required written work!

Thank you for this wonderful essay! I do think there is more reciprocity in the relationship between philosophy and psychology than you address. And that there is a distinction between psychiatry and psychology that is important. But fascinating issue and I’m sorry I missed the think and drink

Hi Kim. Thank you for sharing your thoughts with me! You highlight some interesting points for exploration surrounding psychology versus psychiatry. I would like to take some time over the holidays to discern them more thoroughly. Is there a particular distinction between psychology and psychiatry you would like me to directly address? Also, would you be willing to share a bit more about the kinds reciprocity you are envisioning? Thank you for taking the time to read my work! I look forward to continuing our discussion soon!

Well written essay with the result of stimulating thought. As we all continue to search for the “good life” and what it means it seems we need both the philosophical and psychiatric perspective.

I’m not a philosopher by education, but I am always pondering and questioning behaviors, responses, people and life (as well as a fair amount of introspection). I enjoy discussing “what if scenarios” that others may dismiss because they’re generally unlikely. I enjoyed reading your work here and I’m looking forward to your workshop on the 10th – I’ve never participated in anything like it.

Hi Mellissa,

Thank you for sharing! One of my favorite aspects of the Merlin workshops is the group engagement with “What if” examples. I think introspective thought experiments are a key to the philosophical process, especially for a topic as interpersonal as empathy! I’m looking forward to meeting you on Saturday and engaging with your ideas!