We believe that philosophy is grounded in the here & now and its questions (the things with which it is concerned) are extremely practical & relevant. Our community endeavors include a range of philosophy in the community activities designed specifically around the interests of community members. Some of these are ongoing; others are structured to be stand-alone.

From local shin-digs and collaborative efforts to our ongoing Thinking About Place project, our community endeavors are all about you (and philosophy, of course!).

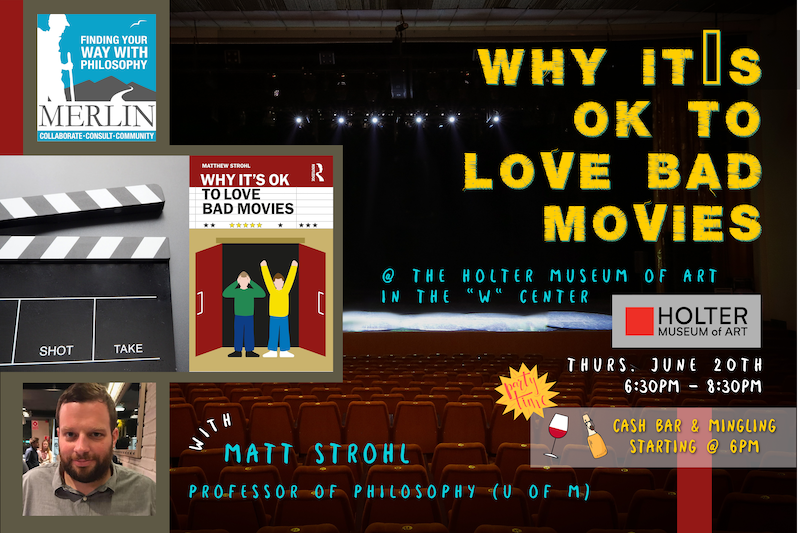

Thursday, June 20th (6:30pm-8:30pm)

Come join us for a fun night of film, philosophy, and community at the “W” in the Holter Museum of Art w/ cinematic bottom-feeder & philosopher Matt Strohl. We’ll consider films like Troll 2, The Room, Batman & Robin, Twilight, Ninja III: The Domination, and a good portion of Nicolas Cage’s films and see if these so-called “bad movies” might actually be key ingredients to a fulfilling aesthetic life.

A documentary & community conversation in support of improved ways to understand, think about & respond to the complexities of homelessness as a community.

Our “Toward a Better Understanding of Homelessness” public philosophy project is a response to ongoing (and growing) housing shortages at home & abroad, and a more general and important call to adequately understand the multi-faceted nature & complexity of homelessness. At its core, the project is an invitation to carefully reflect on these complexities and an opportunity for improved ways of thinking and responding together.

While inquiries into homelessness are not new, making philosophy central (both in terms of approach and questions asked/explored) can be a helpful lens and bring to the fore important considerations for both those experiencing homelessness and those responding to it.

Project Timeline: Interviews and recordings will take place in the summer of 2024 through late Spring/early Summer 2025, film creation & editing in the Summer of 2025, and the film screening & community discussion in Fall of 2025.

Thinking About Place

(w/ Dennis McCahon)

When we get that “sense of place”, what’s going on? What are we “sensing”, and to what extent might it be a shared sense? This project invites to consider these questions and more.

What’s “place”?

Urban design and architecture are often called “place-making.” Save a bit of wildland or

a fragile habitat and we’re saving a “special place.” Montana is the “last best place.”

So again, what’s “place”? What meaning does the word carry through all those roles? Is there a clue in that

old term “sense of place”? What senses are in play? When your sense of place kicks in, what’s going on?

These questions deserve our shared thought, given our shared regard for those increasingly vulnerable

“special places” and our desire for more roundly-considered “place making.” Why not use this page to share some thinking? Here’s an open invitation to take part in a community conversation.

Here’s a bit of what I’ve been thinking about:

- What’s the “place” I sense in Helena? And vicinity? And at our “urban-wildland interface”?

- What does “interface” mean in this case? How many kinds (gradations?) are there? What must be

sustained on either side of the interface so it’ll sustain integrity as “place”? - The classic requirement of architecture (including urban design) is that it provide “commodity,

firmness and delight”; so what does “delight” mean here nowadays? Is it about “place”? - What’s the place-making role of human presence in the urban outdoors — Pedestrian presence? Artisanal presence? Historical presence?

One way to start a conversation about “place” is to pick a favorite example, start describing it, and suggest a few things that make a “place” of it. So, I’ll start.

A chance meeting of assertive bedrock and agreeable architecture on the west side of South Park Avenue, across from the Library and Pioneer Park, never fails to grab my imagination. There’s that dramatic face of tan-colored quartzite, well-defined beds dipping south, just across from the park. It was once sand at the shore of a shallow mid-Cambrian sea, about 350 million years ago. Then a bit to the north, just south of Brooklyn Pizza, there’s that equally dramatic face of reddish rock, born in another sea about 1.4 billion years ago. Between those two faces is an “uncomformity”, a gap of a billion years, more or less.

Bridging that billion-year gap, and linking those two rock faces, is a nice piece of human workmanship—a retaining wall built, about 130 years ago, of a third ancient rock. Once mud settling atop that mid-Cambrian sand, it’s now a layer of siltstone. Reeder’s Gully follows the plain of contact between those layers (a conformity this time). Louis Reeder took rock from both banks of the gully to build structures at those respective banks, but the siltstone in the retaining wall was quarried a short haul away, just uphill from the gully.

Reeder was a sensible builder. In exchange for that handy stone, and mindful that it doesn’t take much cut-and-fill to suit natural human agility, he let his gully keep its character. Though now urban, it still reads as a natural young landform in very old rock. It’s still steep-sided, crooked and rocky, still dramatic on a small scale. Then there’s the architecture. Almost everything about those old buildings — their sizes and shapes, the varying widths of the passageways between them, and the way tho whole bunch follows the pitch and swerve of the gully, goes along with that natural scale of the terrain.

As does the retaining wall. Slung easily along its bank, it’s taken on the visual texture and repose of the outcrops it spans. I like comparing the pattern of joints in that masterful old masonry with that in the raw quartzite below and just above it.

Reeder’s work and the retaining wall exemplify what I suggest as a key to urban “place”—aa mutually stable interface between human works and the defining physical peculiarities of their natural setting. Both sides of the interface are present — integrity on both sides — a clean contact, not a flavorless blend or an indifferent smoothing-over.

“Place”, as a human experience, of course needs a third presence. We’ve got to be there. So, I suggest another key to urban place — continuous pedestrian scale, or, for lack of a snappier term, “walkability”. Walking, after all, is my natural way of moving around, my only way of doing so that keeps me in constant sensory contact with what I’m moving through. On foot I get the immediacy of that interface and of the integrity of what’s on either side of it.

Interface and walkability are both about physical features of a place. I say they’re key because I’m speaking from my interest in urban-environmental design; but there are countless other points-of-view, and many more keys — associative, social, historic, artisanal, accidental (plain good luck) and so on. I want to better know these other keys. I want to learn from these other points of view. I want that conversation. So let me hear from you. What’s a favorite place of yours? How does it work?

Send your observations, ideas, questions and comments to me Dennis McCahon at [email protected]. We’ll add your thoughts here to our community endeavors page & I’ll reply…and we’ll get the conversation going.

A fourth-generation Helenan, self-taught artist, and former Helena city planner, Dennis McCahon has been fascinated by Helena’s architecture for decades. His interests are wide-ranging and deep. Dennis can often be seen walking the trails and streets of Helena, contemplating big ideas about our natural and built environments, history, and art. A self-described urban design geek, Dennis offers a unique “urban environmentalist” perspective — which he defines as a perspective informed by an interest in “walkability” and the “preservation of habitat for curious pedestrians.” To contact Dennis McCahon directly with a question or a comment, please e-mail him at [email protected].

Past Community Endeavors

-

Big Ideas by Little Philosophers (2019-2020)

-

Hayride-Cemetery Rides w/ Ellen Baumler: Pumpkins, Ghosts & Cemeteries (Fall 2020)

-

Science on Tap: Three Thought Experiments that Revolutionized Science (Winter 2019)

-

Flamenco Night at Free Ceramics: Celebrating Music & Community (Spring 2018)

-

Life Enrichment & Wellness Program for Seniors at Touchmark on Saddle Drive (Spring 2017)

-

Downtown Helena First Friday with Aizada Imports: Friendship & Love (Summer 2016)

-

Beat the Heat Philosophy Party (Summer 2016)

-

Earth Day Expo: Helena Community Resilience Project (Spring 2016)

Learn more about some of our other fun philosophy-based community events & socials, including our: